Blog

Thursday August 29, 2019

Coming Soon!

Coming Soon to MediaPrehistoria.com:

The Deer Long-Bone Modification Notebook

My recent and re-inspired replication of Archaic bone pins and other items made from whitetail deer long bones has led me to a point where I feel it is necessary to further document and publicize some of the techniques I use for reducing bones into usable splinter-like pieces called controlled longitudinal fragments (CLFs). These fragments stand in contrast to the broader, short pieces with spiral fractures that are produced through simple smashing, as would be done for the extraction of marrow or for making stock. The Notebook will feature replicated materials, methods of splitting, and variations of techniques and tools used, plus relevant periodic updates. Stay tuned!

A selection of controlled longitudinal fragments (CLFs) produced using the anvil/wedge technique

Two whitetail deer metapodials, one of which has been grooved and split using flake tools.

Friday August 16, 2019

Ostrich Eggshell Beads!

Yeah, it's a real project. New and different to me, though!

Monday August 12, 2019

It Seems to Have Hatched (sort of)

There now seems to be a surplus of ostrich egg shell. What could one do with it?

Wednesday July 24, 2019

Something a Bit Different

Let's see...a pump drill...and an (empty) ostrich egg. What could possibly be going on here?

Saturday July 6, 2019

The “Big Arrowhead”, Retired

If you've seen any of my talks in the last, say, twenty years, there is a good chance you've seen this point. Certainly, thousands of school kids and numerous adults across the southeast have seen it as part of my "12,000 Years in 45 Minutes" program. Made sometime in the mid-1990s, I had intended this banded rhyolite point to become a working tool, and despite some fairly heavy utilization early on, it soon came to reside with the assemblage of other program material to fulfill my need for a dedicated "big arrowhead" prop. For years, it was my launching point (so to speak) for communicating the idea and terminology of projectile point to my audiences ("On the count of three, everybody say projectile point!"). It has taken a few accidental spills off tables, among other abuses, but it survived with virtually no damage. As sometimes happens, familiar objects acquire a level of personal value that exceeds their actual value, and thus I have chosen to retire this pp/k from active service.

Saturday, June 29, 2019

The Art of Self Study

I occasionally catch flak for my habit of studying my own work in primitive tech, but hey, there's plenty of it around and no one else seems to be interested. I've had no takers on my offer, but I've floated to colleagues the prospect of testing some of my former activity areas as a sort of "ground truthing" in the most extreme way – even if I don't recall every detail of what I (or a class under my supervision) did in a particular area, I can provide far more detail than is available from an authentic archaeological site for which no one is still around! And "renewable" modern sites can be invaluable for training field schools and classes in the practice of excavation, while avoiding the risk of destroying ancient archaeological sites.

In 1999, I (as part of the Society of Primitive Technology) participated in the excavation of the Old Rag site, a location on the flanks of the Virginia mountain of the same name, where, for a few weeks in 1972, the late Errett Callahan (1937-2019) conducted a group primitive living experiment. At the time of our excavation, this "site" was nearly 30 years old. We were all excited; in experimental archaeology terms, this was "deep time"! Now, a number of my own activity areas are approaching the 30-year mark.

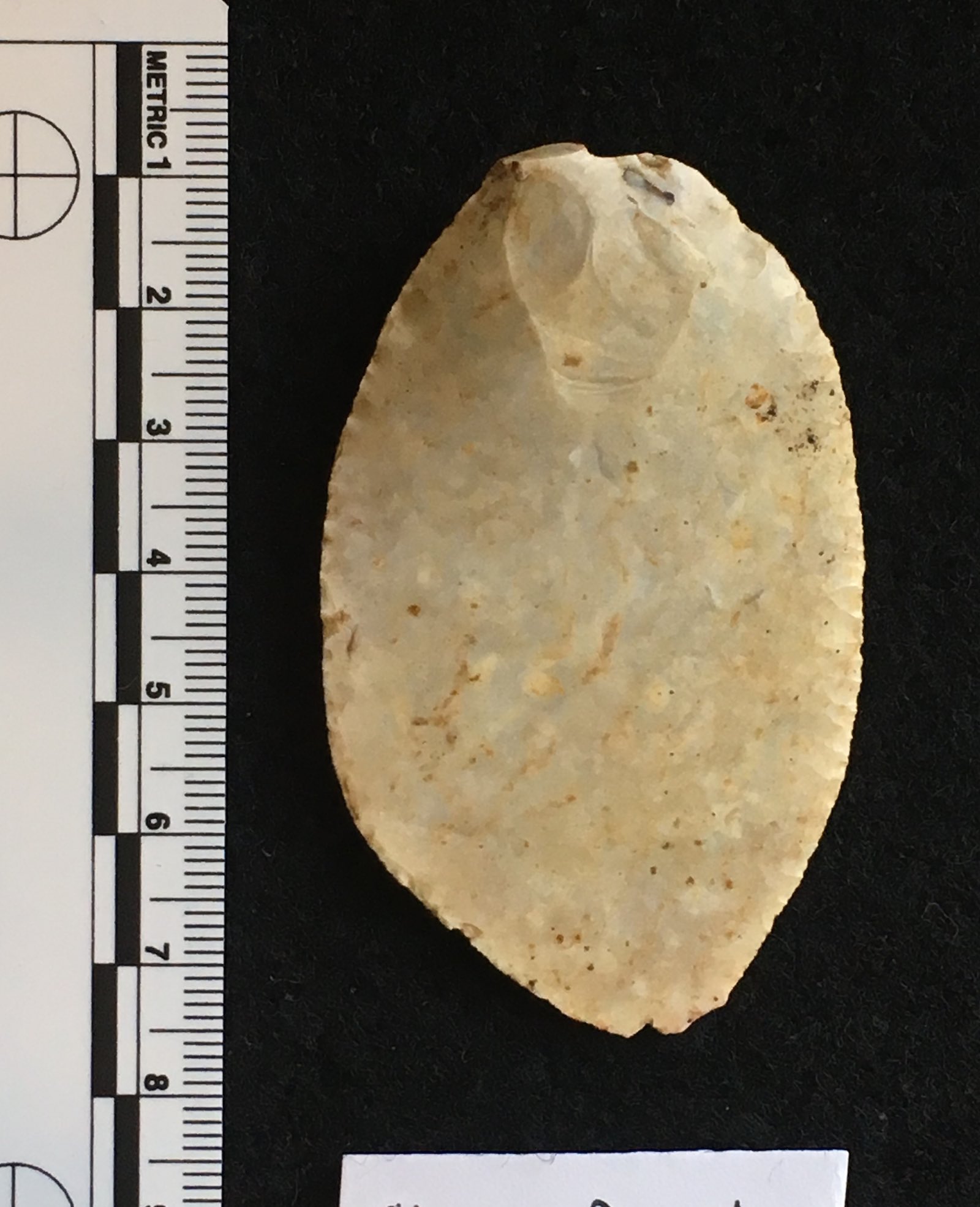

So, without takers, in recent years I've undertaken to collect – and occasionally excavate – some of my areas, using the resulting assemblages as educational aids. After all, many interpretive snags originate in archaeology labs, with analysts who are unaware of the subtle details of lithic reduction, thermal damage, and other common traits exhibited by artifacts. In that spirit, I'm adding these to my teaching collection, a Coastal Plain pp/k and obsidian biface fragment recovered few days ago at the Woods property. They were surface finds in a small area that I used sparingly (and briefly) for knapping during the early 1990s, where only a few other flakes have yet appeared.

Sunday May 12, 2019

Shell Bead Replication on the South Carolina Coast

Yesterday's work area at site 38CH2533. Working with volunteers learning to make beads from the shell of northern quahog (Mercenaria mercenaria), while also trying to improve my technique for roughing out the bead blanks. The purple areas of the shell make attractive beads, and whelk tools are useful for breaking the shell and allow controlled shaping of the blanks.

Roughed-out bead blanks.

Saturday May 4, 2019

Another Atlatl

...Because sometimes you've just gotta make another one. New thrower with composite weight attachment and antler tine hook. The body is hickory wood with ocher stain. The hook needs a little adjustment, but a fair weapon otherwise.

Sunday March 17, 2019

Old Fire-Making Gear

Back after a brief hiatus! It's no secret that I have a soft spot for worn-out fire-making materials. Some of it is memory and sentimentality of things done, some is an appreciation for the effort it represents. A little (pre-) spring cleaning turned up these, a few old hearths and spindles, and a couple of my signature split dogwood bearing blocks.

Friday January 25, 2019

The Upland Late Archaic, Updated

This post hearkens back to the August 18, 2018 post, which featured a fragmentary Paris Island projectile point made of Coastal Plain chert collected on a local (and very sparse) lithic scatter. As stated then, that point caused me to reassess my assertion that the site is Middle Archaic in age, being more aligned with the last phase of intensive Late Archaic upland occupation. After recent heavy rains, I revisited the site, and recovered this more-or-less intact Paris Island pp/k made of Little River metadacite, a metavolcanic material that occurs in east central Georgia. Now with two diagnostic points, the site can be confidently dated to the earlier part of the Late Archaic. Both of these points came from one of two "hot spots" on the site-- in quotes because of the pitifully small numbers of artifacts found. The other spot yielded what appears to be a crude "stubby stem" (Piedmont Allendale) pp/k, leaving open the likelihood that the site also contains a late Middle Archaic component.

Saturday January 19, 2019

Working Out Archaic Bone Pin Design

The four completed bone pins shown as plain blanks in the January 2nd post. These were practice for working out methods for successful engraving. Three have charcoal pigment applied to the designs, except for the second from the right, which is colored with red ochre. This is also the longest of the group, 6 3/4" (71 mm).

Friday January 11, 2019

A Tool Kit Revisited

This buckskin bag and most of the tool hafts were created in 2002 for the filming of "They Were Here: Ice Age Humans in South Carolina" by South Carolina ETV. This program focused specifically on the pre-Clovis aspect of the Topper site (38AL23) in Allendale County, SC.

My current work involves the production of Late Archaic bone pins and other bone/antler items, and the use of small stone tools (microtools) seemed most appropriate for the task of engraving them. Consisting primarily of simple compression hafts and slip-ring "x-acto knife"-style hafts, I resuscitated and upgraded this kit for the job.

The TV program evidently still appears occasionally on SCETV, and is available for purchase at their site.

The current incarnation of the tool kit, and some bone items.

Me demonstrating the use of a bend-break (pseudo-burin) tool to work antler. This photo was used in my article "Smashing Success: Pleistocene Lithic Replication in South Carolina". Photo by Daryl Miller.

Wednesday January 2, 2019

More Bone Pins

New Year's resolution: Make more Archaic bone pins! Spent a portion of my day making some blanks.

Wednesday, November 21, 2018

Savannah River Projectile Point/Knives: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Making up a set of nine knives for use in the ongoing bone processing project, with an eye towards making the experience a bit easier for those who have limited experience in using stone tools. As the title suggests, these bifaces (all variations of the Savannah River/Late Archaic stemmed style) range wildly in quality, some knapped from pieces of stone that were never destined to be pretty. That's OK, as they are likely to lead brief, sad little use-lives as they endure much wear and damage as saws for splitting deer bone (see previous blog post). Some are lumpy, bumpy, and step-fractured; others are merely flakes modified enough to fit the pp/k style. When you're actually working with the stone tools you create, there's seldom any reason to let a biface go to waste, no matter how homely!

Top, three rhyolite points. The middle example is made on a thin, flat flake. The rest are Coastal Plain chert of various forms. The lower left and center points both have thick step-fractured "stacks" in their middle portions, resulting from coarse, grainy areas in the raw material. The bivalve fossil visible in the lower left example creates and arc-like void that goes entirely through the point, creating an additional liability.

The finished hafted tools, in no particular order. Socketed handles made of tulip/yellow poplar, oiled and stained with red ochre (why not make 'em as pretty as possible?). Once the socket is drilled/gouged out to a snug fit, the point base is inserted, and the tip placed on a log or stump. The proximal end of the handle is then lightly tapped with a mallet. This drives the stem of the point into the handle, creating a tight, custom fit--provided the haft doesn't split or the point tip doesn't break off. For durability, these are secured with hide glue rather than my customary pitch glue. Socket hafting requires no fiber binding, and has precedent in Late Archaic tools found at Stallings Island (GA) and elsewhere.

Tuesday November 20, 2018

Bone Working with Stone Tools

Animal bone can be worked in virtually any state, but fresh ("green") bone is substantially easier. I prefer to extract the longest possible pieces, especially for making bone pins, eating utensils (chopsticks), and awls, so careful grooving of the bone prior to splitting is advisable. Shown here are two photos I took of this process at the Chehaw Traditional Skills event last month.

Top, unmodified rear cannon bone (metapodial) from whitetail deer. Bottom, the other rear cannon bone after being grooved on both sides and split initiated with a chert flake wedge. Also shown: sinew extracted from the foreleg and some of the flakes used.

The work area with leftovers, more sinew, and flake tools used.

Sunday, October 28, 2018

A Rare Memory

I found this today--a note from Steve Watts--while going through a box of work material that I'd neglected in my workshop for a number of years, probably from sometime during our first couple of years here at Meadow Lane. Steve and I had both been at an event (Hammond School, I seem to recall), and leaving before me, he placed it on the front seat of my van. I inadvertently stuck it in the program box, where it remained until I found it again today. Happy trails indeed, brother.

.jpeg)

Wednesday October 24, 2018

An Interesting Raw Material

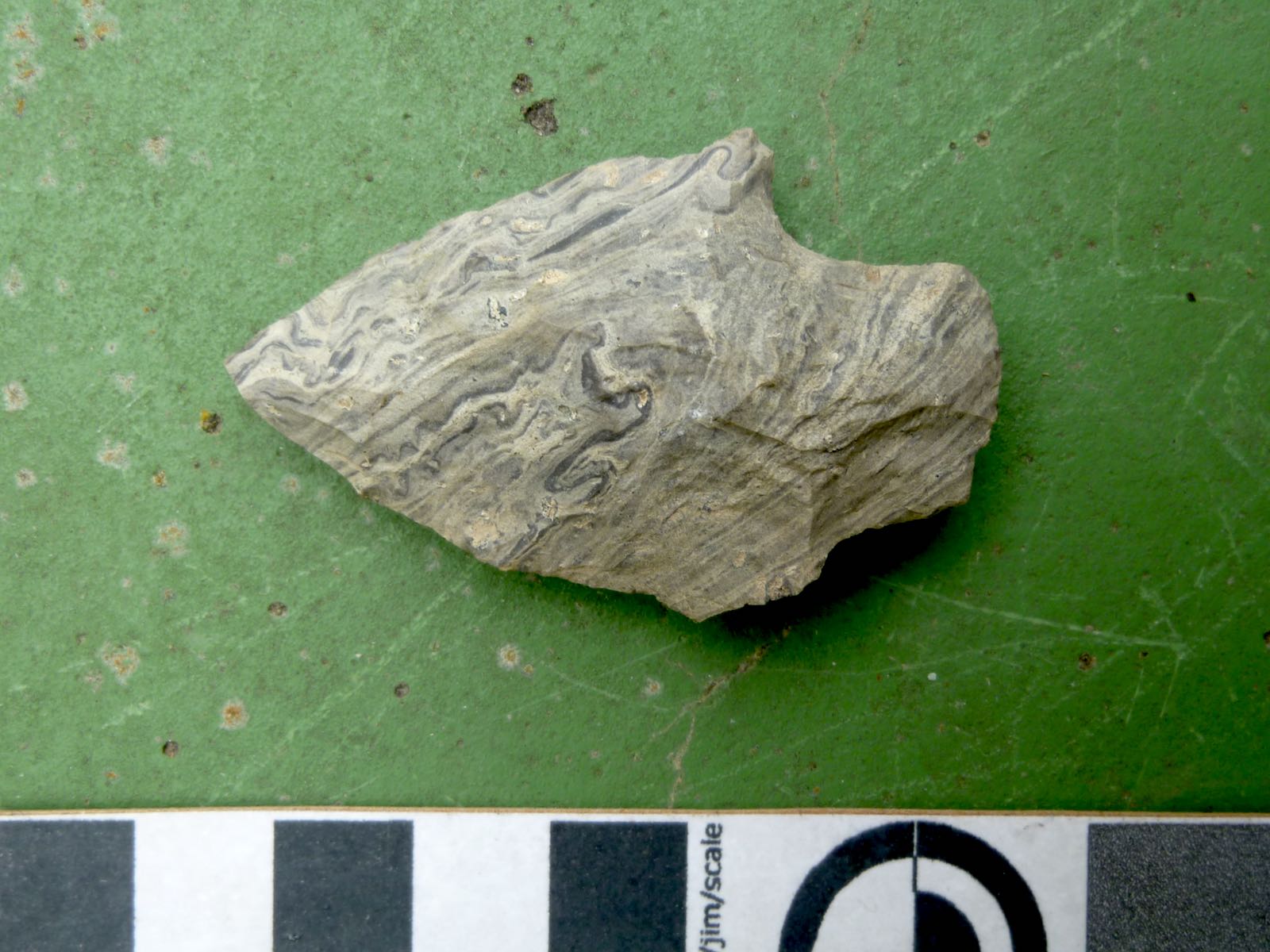

This point was recovered from an (as yet) unrecorded site just down the road. An atlatl weight (bannerstone) fragment was found on the site last year, and lacking diagnostic bifaces, the form suggested that it was from the early part of the Late Archaic, probably Paris Island time period. The site was recently re-cultivated as a wildlife food plot, and in addition to the usual amounts fire-cracked rock (FCR), two diagnostic points were found a couple of weeks ago--one broken quartz point, and this one. The base of this point is slightly mangled, and was originally rounded (a la the Paris Island type). Also, one shoulder is also damaged, and the corresponding blade edge has been burinated, indicating an impact fracture.

While familiar metavolcanic materials (rhyolites, and the "Little River dacite" from eastern GA) are not unknown here, I have noted that some materials simply do not conform to the known varieties. Having been found a considerable distance from the classic regional metavolcanics, and practically on top of one of the defunct Piedmont fault zones, this point appears to be made from a local mylonite, a fine-grained rock formed from the crushed and smeared interface of massive fault blocks sliding against one another. (The rolled-up streaks are characteristic of a mylonite, and help differentiate it from classic flow-banded rhyolite.) Mylonite and hornfels occur sporadically across the Piedmont, and can be quite limited in distribution, sometimes just a small vein of rock weathering from a creek bed, for instance.

Sunday October 14, 2018

My Life in the Gig Economy: The Mammoth in the Room

This post addresses a topic I've pondered at great length over the years: subsistence. Now, you may be thinking I'm going to regale you with a fantasy about mammoth hunting or some similar pursuit, but no. This post has to do with making money. Which, in a roundabout way, qualifies as subsistence in that it helps provide food, shelter, clothing, and other necessities.

For many years I've been in a form of self-employment that I only recently heard called "the gig economy", which, to the best of my understanding, refers loosely to those of us who make our living as sole-proprietor/contractors. People are sometimes appalled when they find that I charge $500 and more for a day of educational/demonstration/media work (archaeology and writing are a bit different, on an hourly scale), especially since I make my living with simple fare like sticks and rocks. Also, we are so familiar with the cost-absorbing behemoth of the industrial/corporate economy that we are taken aback when we come face-to-face with the economic realities of people running small businesses and sole proprietorships. Where do we small-timers get off charging "so much" for our services?

Let's start with one of the main cash-sucks: travel expense. For those operating within the structure of institution—be it corporate, governmental, academic, or other—it is practically a given that work travel, conferences, and associated expenses are provided outright, or are reimbursed, and time thus spent counts as work time. Not so for the sole-proprietor/contractor. Although tax-deductible, all of this comes right out of our pockets, paychecks, and time. Here's a recent example: I was offered $250 for a one-day show. Now who couldn't use an extra $250? Even at this point in my career, I was naive enough to think that I might break even on this. So I ran the mileage numbers, the shortest distance from my home location being 232 miles, one-way, for a round trip of 464 miles. At .54 per mile (lower than the current rate, I know, but just for reference), the mileage alone for this event would've been $250.56, my paycheck shot to hell right there. You might think, "Well, your old jalopy is paid for...isn't mileage a moot point?" Maybe...not. I've still got to put gas in the thing, maintain it, keep tires on it, and insure it so I can reliably get from one event to the next. And if I continue in business, someday I will need to replace it. So yeah, mileage is a thing. It's real, and important.

And then there's the usual per diem: you've got to eat and sleep. Although in this example, lodging was included in the offer, but this was in a "group camp cabin", basically a dormitory setting. I'm no spring chicken, so I'm long past the point in my life where I'd be willing to sleep in the car to save money; I don't want to look like I slept in my clothes when I show up, and I sometimes just like to have a little privacy either before or after an event. The prospect of lodging with strangers made the Econo-Lodge up the road start to look pretty inviting. If you don't want to have to fumigate your motel room prior to inhabiting it, prepare to spend somewhere in the neighborhood of $100 a night (which is the rough GSA average for lodging here in Georgia). As for food, if you don't want fast food three meals a day, you can expect to drop an average of about $50 per day for chow ("meals and incidentals", as it's called).

So let's say I'd been offered a more typical $500 for this one-day event, rather than the $250. Even if I'd opted for a long Saturday culminating in a 4 1/2 hour drive home at the end (rather than a second night there), I've already shot $250 on mileage and about $150 on food and lodging. Out of that $500 check, that's $400 of it gone already! Fine, you say...that's $100 profit. Sure, but for a 7-hour day (not including set-up and take-down, or the drive home, just the "on" portion), that's an hourly rate of about $14.25. Yeah, that's fine if you're an aspiring noob—not a veteran practitioner and specialist. Not to mention the time spent preparing, gathering, sorting, packing, unpacking, setting up, taking down, driving long hours, being away from family, creating content, and doing background research. I could easily make as much per hour working at a burger joint AND not have to spend long stretches of time far from home. So if you contact a self-employed artist (or speaker or performer) for an event, don't be surprised that they charge for their services, nor be surprised by the amount they charge.

After long years of struggling against a natural desire to not charge for my services (where's that MacArthur Fellowship, anyway?), I eventually reached a point where I realized I could unwittingly lose money on something which, at first blush, seemed profitable. I also realized that there had been instances in which everyone else involved in a project was doing so within the scope of their paid employment...except me. It's my fault for not being more astute, but formerly, when roped into someone's pet project without mentioning money, I used to naively assume that everyone else involved was also doing it pro bono. It can be a real buzzkill to have the dawning realization that your current cohort of associates are in the midst of their workday, taking mandated breaks and such while you're...not. If I'm not on the clock, I'm not getting paid. Which brings up the "exposure" issue. Finally, if you run events and wish to hire freelance contractors such as myself, spare yourself some inadvertent embarrassment: Never, ever (this, coming from a guy who never, ever uses the phrase "never, ever") tell anyone in the gig economy (especially primitive skills) that they can participate in your event "for exposure". You're not fooling anyone, you're just being a transparent cheapskate. There is a place for free or break-even programs, such as small groups who genuinely have no funds, friendly mutual arrangements, start-up events, community involvement, charities, and short local talks; also, sometimes the perks far outweigh the financial profit, so it's a judgment call. Big festivals and events generally have budgets for entertainment and displays, though. My standard reply to the exposure offer is to quip that "you can die from exposure", and then politely decline.

So if you're in the gig economy and you're reading this, I encourage you to be always conscientious and considerate in your business dealings, but be sure you're up front about the mammoth in the room, talk bluntly about money, get your due and ensure you are treated fairly.

Saturday October 13, 2018

Yucca Harvest

The various species of yucca are suited to a range of uses, from their soapy roots (not edible, that's yuca --casava-- from a different plant, Manihot esculenta) to the fibrous leaves (for cordage), and the semi-woody stalk that is useful for friction fire-making and expedient handles for stone tools. The flowers of many species are edible (and tasty) as well. This member of the Asparagaceae (formerly classified as Liliaceae) sends up a flowering stalk during the growing season. As the season progresses, the flower stalk and associated leafy stem die, to be replaced the following year by new shoots arising from the roots. Shown here is a specimen of Yucca filamentosa (probably var. flaccida) growing along a fence row with leaves that have recently died back and in good condition, and the woody stalk.

Carl examines harvest-ready yucca leaves and stalks.

Close-up of the dying leaf rosette and stalk base.

Wednesday October 03, 2018

Turtle Shell and Dermal Patterns as a Possible Origin of Swift Creek Pottery Designs

© Scott Jones, 2018

(To cite this post, see below*)

Much ink has been spilled and verbiage expended on the origins, development, and interpretations of Swift Creek pottery stamp designs. They have been viewed as highly stylized and very nearly hallucinatory depictions of various naturalistic forms, or as independent invention of entirely abstract or mythical fancy. I am less concerned about what these designs ultimately became; my interest lies in how these designs may have been initially conceived.

It has been my lot now for well over 30 years to replicate and document the everyday processes of the prehistoric past through primitive technology, experimental archaeology, and the nexus created by human interactions with the natural environment. With pottery technology being a relatively new wave in North America during the Woodland period, Swift Creek ceramics of the Middle Woodland date broadly from around 2000 years ago to about 600 AD. These wares were preceded by 2500 years of pottery during the Late Archaic and Early Woodland, much of which featured relatively simple surface decoration, from punctations to various markings created by cordage or various textiles (nets, fabric). We will likely never know precisely how or why – beyond the human creative imperative – these earlier, simple designs eventually shifted to complex, artistic ones, but turtle shell and skin patterns may provide clues to their origin.

A few years after I began considering beavers as a keystone species engaged in a commensal relationship with Native Americans, my explorations of beaver ponds caused me to turn my attention to the many other animals that follow the arrival of beavers, notably the pond and river turtles. So numerous were they that it is safe to say that these reptiles are optimally suited to beaver-created habitats. Although I considered myself to be generally well-versed in the native turtles of the southeast, I began to research them and improve my identification skills. Having made numerous pottery stamping paddles, as I studied the patterns evident on their shells and skin I was struck by the resemblance of their markings to certain complicated-stamped designs. The few people to whom I mentioned this didn't laugh or raise eyebrows, nor did they wholeheartedly agree; this ambivalence is perhaps the reason I remained unmotivated to go public with this notion until now. I sometimes work best under the pressure of criticism.

My initial thoughts on this potential relationship between turtles and Swift Creek pottery were derived from the (perceived) superficial similarity. At first I dismissed the idea of turtle-shell-pattern-as-pottery-design as a mere coincidence of nature and stone age culture. In the intervening years, as I considered (and tried to identify) the great variety of sliders, river cooters, painted, map, and other pond turtles, I also reflected on the odd and significant role of turtles within Native American culture. I also considered the possible reasons why, among all the intricate patterns that occur in nature, those belonging to turtles could rise to primacy.

Apart from a superficial similarity between their shell/skin patterns and pottery stamp designs, what is the cultural significance of turtles? What case can be made on practical or ideological grounds for the adoption of turtle patterns for ceramic designs? For starters, they occupy an ambiguous and liminal space in Native American culture and cosmology. (e.g., Hudson, 1976: 139). Without delving into ethnographic detail, it is well known that turtles in general were widely revered in historic Native American lore, perhaps most famously as the bearer of the terrestrial world.

On the other hand, their bones are common among the faunal remains on archaeological sites, and they were used extensively for food in historic times, suggesting they were collected and eaten with impunity. For instance, Skinner (1913, cited in Swanton, 1946) notes that the historic Seminoles are reported to have roasted them alive. Thus, the available evidence suggests that the role of these common reptiles in Native American mythology was overprinted by their practicality as a food source. Consumption of turtles would also provide a source of shells for containers, rattles, and other items of everyday and ritual use. The use of turtles for food would put them in close contact with humans, who would likely be intrigued by the shell/skin patterns – even as they were being preparrd for dinner.

Also, few things in nature are so obviously bowl-like as are turtle shells; it could be said that they are in elite company in this regard. In a pre-ceramic Archaic world, a turtle shell may have been a valuable possession. Close and regular proximity to turtles as either food or vessels would have made their exterior patterns familiar features of everyday life. I find it difficult to believe that their bold, curvilenear patterns – often convoluted and exhibiting nested or concentric teardrop/snowshoe shapes, rings, or other elements – would not have been incorporated as decorative design elements.

An observation to be made here is that turtle patterns are often most pronounced on juvenile examples, or on the cleaned shell of dead individuals. The shells of turtles become covered with algae with age and maturity, and even after cleaning, the patterns of older specimens are often less distinct than those of young ones. Juveniles are easily caught, and cleaned shells of food turtles would likely be cleaned prior to use. Either situation would allow for the close examination of shell patterns. Tangentially, the plastrons (lower shell) of juveniles of some turtle species often display intricate and highly symmetrical patterns that are perhaps most reminiscent of pottery stamp designs.

In conclusion, I am not suggesting that Swift Creek (or other) stamp designs are in any way faithful representations of turtle shell or skin patterns. What I am suggesting, however, is that turtle patterns provide a cosmologically significant yet plausible, natural-historic link to the abstract world of stylistic innovation during the Middle Woodland. Even if these designs developed over time into meaningful abstractions far removed from their original source, that source (the turtle) is a real-world starting point.

Swift Creek pottery designs. From Wauchope (1966), Archaeological Survey of Northern Georgia with a Test of Some Cultural Hypotheses. Memoir, 1. Washington, DC: Society for American Archaeology.

Red eared slider. Creative Commons image

Red bellied cooter juveniles. Wikimedia Commons

Note: I am using "labeled for reuse" images of turtles to avoid infringing on copyright, thus the ones shown are not necessarily the best examples or regionally most appropriate. I encourage the reader to do his/her own image search, consult a book, or – heaven forbid – examine actual turtles.

*Citation

Jones, Scott. "Turtle Shell and Dermal Patterns as a Possible Origin of Swift Creek Pottery Designs." Scott's Blog, 3 October 2018, http://mediaprehistoria.com/blog/#024

References cited

Hudson, Charles1976. The Southeastern Indians. University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville.

Skinner, Alanson

1913. Notes on the Florida Seminole. American Anthropologist (N.S.) 15: 63.77

Swanton, John R.

1946. Indians of the Southeastern United States. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin Number 137. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Monday September 17, 2018

More from the Shell Ring Diaries: Another Bone Pin

I learned to work bone early in my career, and it's been years since I've been intimidated by the challenges of working this material, but here I am invoking some of the streamlining processes I've discovered over the years. In working on this bone pin ("crutch-top" style, center) today, I used an improvised live oak jig. This is essentially a section of heartwood with a lengthwise seasoning crack, and live oak being what it is, the crack is fairly stable and unlikely to continue to split. Laid lengthwise along the split, the bone pin blank becomes more stable than it would be on a solid surface, allowing for ease of abrading or scraping (as was done with the large square-edged flake, right). Also, flakes and bifaces can be tapped into the split to create a stationary "bench tool" for scraping and planing by drawing the bone across the stone edge. This makes use of minimal stone and available materials (flake driven into cleft, left). This topic and more are covered in "The Prehistoric Workshop" chapter in Postcards to the Past. Length of pin is about 11 cm, or just over 4 inches, guitar pick for scale.

Monday September 10, 2018

Beavers, Native Americans, and Archaeology

By 1999, several years had passed since beavers had moved into my small creek at The Woods homestead, and the marvel with which I viewed their environmental handiwork had become strongly integrated into my teaching. I understood that prehistoric Native Americans of the southeastern Piedmont would have recognized (and utilized) upland beaver ponds as small-scale wetlands in those areas between major rivers. That same year, I acquired a copy of Charles H. Wharton's The Natural Environments of Georgia (1978).

A single line from Wharton's work inspired me to expand my thinking about beaver workings beyond mere opportunistic utilization. I began to view the presence of beaver ponds as a potential influencing factor for the location of archaeological sites. Wharton says, "I suspect, on smaller streams in the mountains and Piedmont, that the Indians may have utilized the silt-floored and treeless beaver ponds as corn fields, allowing beavers to reclaim them periodically" (1978: 103). My vision of preferential exploitation of beaver habitats as upland mini-wetlands was, and remains, inclusive of all time periods, extending across nearly the entirety of southeastern prehistory. My original draft from 1999 was entitled "Rodents of Change: The role of Castor canadensis in the Alteration of Landscape and Culture". As I further developed the key themes, I changed the title to "Gnawing Desire: The Role of Beavers in Prehistoric Culture", which was published in the Bulletin of Primitive Technology in 2001 (22: 54-59). Although my ideas were clearly oriented to my home in the southeast, I tried to make the Bulletin version somewhat more broad-based for a wider regional audience. This is the version offered here (click to download PDF version), used by agreement with the former editor. (Also, back issues of this and other volumes are available at www.primitive.org.) Other versions of Gnawing Desire were later published in Early Georgia (2003: 31: 53-64), and in A View to the Past (2008: 201-211). It was my original work and Bulletin article that inspired the collaboration between Mark Williams and myself to write a paper for the Southeastern Archaeological Conference in 2001, addressing the likelihood of beaver impoundments as influencing settlement patterns for late Mississippian (Lamar) peoples. This paper, entitled "Lithics, Shellfish, and Beavers", was also included as a chapter in the book Light on the Path: The Anthropology and History of the Southeastern Indians (Pluckhahn and Ethridge, eds. 2006).

Tuesday September 04, 2018

And Now for Some Cheat-and-Chip

"Don't paint all flintknappers with the same brush" is practically a mantra for me, meaning that there are different levels of skill and approach to the craft. I'm known to be one to work with difficult and poorly understood materials, working in a more-or-less authentic way in the interest of learning and research. But sometimes you've got to take a walk on the wild side. This knife, impressive as it may be, is not the product of studious bifacial lithic reduction. I pressure flaked it entirely from a slab of obsidian sawed on a lapidary saw, in the manner of much contemporary commercial knapping. The blank (several, actually) was obtained from a friend, so that I could fulfill an obligation (a knife) to a third party.

Monday, September 3, 2018

A New Pottery Paddle

I was intrigued by this Early/Middle Woodland sherd from South Carolina. Though it is somewhat weathered, I discovered that it is a variety of Deptford Check Stamped with the check pattern interrupted by areas of straight lines. The paddle with the design (as I interpret it) is shown in the middle photo, and a test patty of marsh clay, which has not yet dried sufficiently to fire. For the pottery-paddle obsessed: The grooves in the paddle are relatively deep and V-shaped, cut in with stone tools; you will also note that the lands and grooves on the test clay are flat. The implication? The stamped design you see on pottery isn't necessarily an accurate representation of the paddle itself.

Wednesday August 29, 2018

Avian Gastroliths as Artifacts

Some years ago I pioneered and promoted the idea that gastroliths-- gizzard stones-- from large birds should be present (and recognized) as artifacts on archaeological sites. I won't go into the details here since I covered the topic in the Bulletin of Primitive Technology (2010, no. 40: 33-34) and also included it in Postcards to the Past (2015), but I picked up this one today from a site (9OG480). An exceptionally smooth quartz pebble less than a centimeter long, it caught my eye on the soil surface of an eroding hearth feature. It is not surprising that these "artifacts" are seldom recovered, both because of their small size (often overlooked and/or they fall through 1/4" mesh screens during data recovery) and that they aren't flashy or obviously manufactured. Nonetheless, they have the potential to refine our knowledge of the subsistence practices of past peoples.

Monday August 27, 2018

Thinking About Late Archaic Pottery (Again)

Being an Archaic kind of guy, pottery is not my strongest skill. It is nonetheless a remarkable craft, and I delve into it from time to time, often with a (predictable) focus on Late Archaic forms. About twenty years ago, my interest lay in fiber-tempered (Stallings Island type) ceramics, but my recent work on the South Carolina coast has piqued my curiosity about the Thoms Creek type. Shown are two small bowls made of marsh clay collected near Edisto Island, SC. The naturally black clay--gathered from a relict marsh creek bank-- was used as-is without the addition of any sort of temper, which is consistent with the sherds examined at the site. The surface treatment on both was done with the shell of a marsh periwinkle (Littoraria irrorata), the bowl on the left decorated with crescent-shaped indentations created by using the edge of the shell opening; the one on the right shows punctations made by using the pointed spire of the shell. The periwinkle shell is shown in the center of the photo; to its right is an ark shell (probably Noetia ponderosa), used to scrape the interior of the vessel; and flat oyster (Crassostrea virginica) as a smooth-edged scraping/shaping tool. These shells lie on a pottery paddle made from a section of the leaf petiole base of sabal palm. In the foreground is a conventional, undecorated wooden pottery paddle. This side project is only half done...the pots have yet to survive being fired!

Sunday August 19, 2018

Old Dog, New Atlatl

Revising some of my long-held dogma regarding atlatl design. Despite my usual preference for weighted, flexible throwers in the 22"/56 cm length range, I'm revisiting some concepts regarding shorter, rigid ones for launching slightly stouter, heavier spears. Newly minted atlatl here made of chinaberry-— not a native wood, I know, but pretty nonetheless— 15"/36 cm long, antler tine hook.

Saturday August 18, 2018

Last Gasp of the Upland Piedmont Archaic

When, in 2010, we moved the 20 or so miles from the Woods to the Winterville location, it seemed like an apples-to-apples relocation. I fully expected to find myself once again in an area rife with lithic scatters. I was wrong: instead of being in the high uplands within a single drainage, the current residence lies exactly on the divide between the Oconee and Broad Rivers. This is evident if one drives from downtown Winterville to US 78 on the Arnoldsville Road, onward to Lexington, and then southward on GA 77 to Union Point—this route, which follows the old Seaboard System Railroad, scarcely crosses a single creek. Despite much lore about such divides being preferred "Indian trails", the reality is that they were thinly occupied in prehistory, and archaeological sites are often scarce.

I've adjusted my expectation of what constitutes a site, with subtlety playing a major role. This is demonstrated by a site (as yet officially unrecorded) that lies along a wooded and eroded pasture edge across the road from our house. Over a period of several years I have collected this sparse lithic scatter: a flake here, a chunk of diabase FCR there, a scant few (maybe 4?) bifaces and pp/ks, some made from the marginally workable local quartz. (I urge the reader to consider the source here: when I say quartz is "marginal", it qualifies as "unworkable" to virtually anyone else.) My sense was that the site is Middle or Late Middle Archaic in age, based on the assemblage and the small number of ovate bifaces and points. But last week, I recovered this mangled Coastal Plain chert pp/k base. Despite being damaged, it is consistent with the slightly later Elora/Paris Island point types, both of which date to the early part of the Late Archaic. These types represent the last manifestation of the intensive occupation of the high uplands of the Piedmont, after which the focus for the classic Late Archaic (Savannah River period) shifts to more riverine environments. Paris Island period artifacts are to be expected in the uplands here, but I am a bit surprised to find them on multiple sites; earlier this year, I recovered a fragmentary atlatl weight on another site a few hundred meters to the west of this site. The site yielded no diagnostic points, but the weight is of a type associated with this time period. The pp/k pictured is made on an older point, and the remaining intact shoulder/barb is weathered, and shows differential patination on both sides.

Sunday August 12, 2018

A Slate Knife

Apart from heavy tools like axes and adzes, ground stone tools (including knives) are poorly documented in much of the southeastern U.S. Atypical forms do, however, occur sporadically in late prehistoric Lamar contexts, generally made of schist or other local Piedmont materials that split readily into relatively thin slabs. Here I have selected a thin scrap of slate requiring minimal modification to make a knife. This was done by grinding and shaping the edges on increasingly finer grades of stone, with a final edge polish done with wet charcoal. Edge polishing is not done purely to impart keenness--it renders the relatively soft stone somewhat more resistant to chipping or breakage, much in the same way that basal grinding strengthens considerably the haft areas of Early Archaic and Paleoindian projectile points. These knives are not suitable for use on hard materials such as wood, but perform well where a long cutting edge is desirable for processing soft materials such as meat or vegetation. Obverse and reverse shown.

Wednesday August 08, 2018

Experimenting with Shell Tools

In addition to Late Archaic bone pins, part of the current project involves replication and general experimentation with tools made of marine shell. I have found that chisels and gouges are often difficult to make and problematic to use. Bone and antler have long been my preferred material for working green or soft wood, but these also have limitations. Marine gastropod shell is impressively tough, and holds an edge extremely well. Shown here are two small examples of knobbed whelk (B. carica), both of which have been sharpened on the base/anterior portion of the columella. The whorled spire portion of the shell gives an impression of fragility, but it is quite durable and will withstand being pounded with a hardwood mallet (bottom). Here, a mortise is being cut into a section of green sweetgum to accommodate the greenstone celt blade.

Thursday August 2, 2018

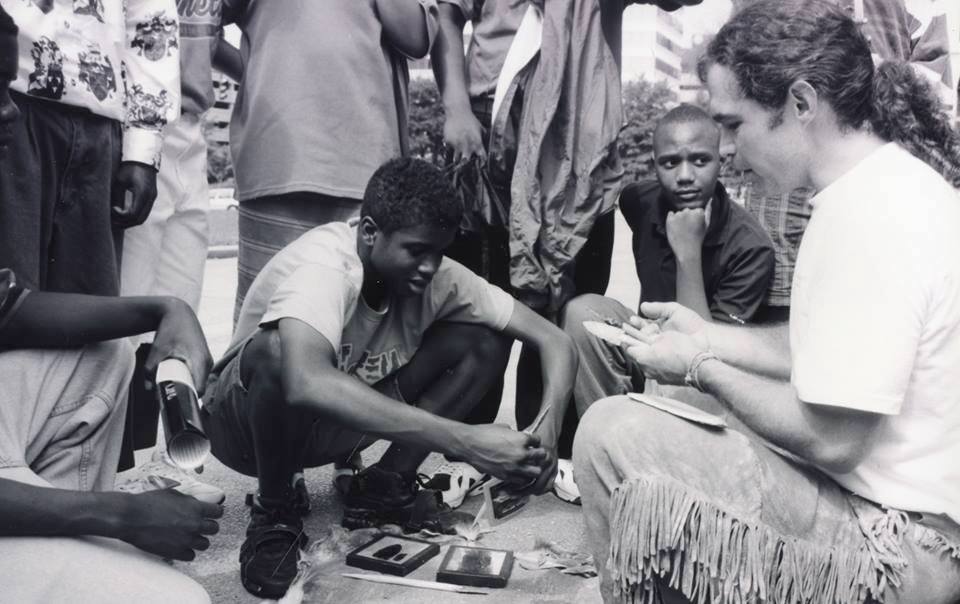

An Archival Photo

I've been at this for a while. An archive photo of me (on right) sometime in the early 1990s, sent to me by the Archaeological Society of South Carolina. Probably from one of the ASSC's Fall Field Day events.

Monday July 30, 2018

Arrow foreshaft

Cane arrows can be foreshafted in the same manner as atlatl darts, but with some adjustments. Instead of being easily removable and replaceable, arrow foreshafts are best as a permanent installment. This one has been shouldered in such a way as to fit precisely into the distal portion of the arrow shaft. It is ultimately inserted, glued, and bound into the arrow. The arrow point can be hafted directly into the cane, but the wooden foreshaft allows for the adjustment of the weight and balance of the arrow.

Saturday, July 28, 2018

Archaic Bone Pins Revisited

Early in my career I became aware of the significance of bone as a material for utilitarian and decorative items. At the time (the late 1980s), Middle and Late Archaic bone pins were a hot topic, as their black market value had soared. I made a number of them around that time, learning to decorate them appropriately with a simplified primitive version of scrimshaw. Over the years, bone pins— the precise function of which is unknown, despite much speculation— remained part of my technological repertoire, but took a backseat to practical tools such as awls.

My recent archaeological work on a coastal shell ring in South Carolina, however, has thrust these beautiful and enigmatic artifacts yet again into my thinking, and I am back to replicating them. The decorated awl-like one in the center of the photo was completed yesterday, the bold incising filled with charcoal-tempered pitch for permanence. Part of my task is to break down the stages of manufacture and decoration, and document this multi-step process. In case you're wondering, yes, the four bound pairs on the left are chopsticks. And yes, I can use them.

Friday, July 27, 2018

Fletching (Part 2)

The finished helical fletching on the arrow (left) and atlatl dart (right). I opted to bind these with linen thread rather than sinew, and secured with hide glue.

Wednesday, July 25 2018

Fletching (Part 1)

Two pairs of feathers...whatever could these be for? Fletchings, of course! I covered southeastern ("Cherokee") helical two-feather fletching in a six-photo instructional panel in A View to the Past, so this isn't strictly a tutorial, but this simple yet underutilized method deserves a bit more exposure. The white pair (top) are domestic goose, the curvature of the shaft (rachis) indicating they are from the same wing, which, when applied to the projectile shaft, will impart the proper stabilizing spin on the projectile--an atlatl dart, in this case.

An examination of the dark pair (bottom, from turkey) will show they are from opposite sides of the bird. "But Scott", you may ask, "don't you say to ALWAYS use feathers from the same side or wing of the bird?" Generally, yes, but this is the exception that proves the rule; both of these feathers are straight, symmetrical, and the vanes of both are similar in size and thickness, making it possible to use these together for arrow fletching. The second photo shows both pairs with the vanes and shafts trimmed in preparation for attachment to the dart and arrow.

Tuesday, July 24, 2018

Some Early Archaic Foreshaft Replications

I no longer officially make reproduction exhibit items, but I agreed to make a small number of items the Edisto Island Museum, as well as compose the exhibit text and provide some source images of my replications. This photo shows four of my Early Archaic foreshafts. The top two in the first photo are among my oldest ones, made sometime around 1990 (the upper one is hafted using pitch, the other with hide glue). The lower two are recent, with the bottom example on track to tip the atlatl dart for the Edisto exhibit. The second photo is a closeup of the business ends.

Monday, July 23, 2018

A Favorite Thing

A Savannah River pp/k I made sometime in the early or mid 1990s. The material is banded rhyolite. For a time, it was just another large biface I'd made, and early on it saw a fair amount of hands-on use. At the time, however, I needed a "big arrowhead" to help introduce the projectile point concept in my "12,000 Years in 45 Minutes" show, and it fit the bill admirably. It became integrated into my school program material, and well over two decades of handling and occasional use have given it a lovely patina, making it an artifact (of sorts) of my work and career.

Saturday, July 21, 2018

The Kombewa Technique (part 4 of 4)

Schematic showing Kombewa flake production.

José-Manuel Benito Álvarez/Public domain image/Wikimedia Commons

Friday, July 20, 2018

The Kombewa Technique (part 3 of 4)

Side view of the flake tool. Bulbs of force are evident on both faces (at top).

Thursday, July 19, 2018

The Kombewa Technique (part 2 of 4)

Reverse of the flake tool posted yesterday. Note that this side also has a bulb of force (and erailure scar) at top. Retouch is also more evident on this side.

Wednesday, July 18, 2018

The Kombewa Technique (part 1 of 4)

As nearly always for me, the most interesting artifacts aren't big, flawless projectile points. So no one will be surprised that I was most intrigued by this artifact from a collection at the 2017 Athens artifact show. In the wake of the interest and discussion about it, I thought it would be worth publicizing the little-known technique by which it was manufactured. Not unlike the strategically complex Levallois technique, this artifact (a carefully retouched flake tool) was made by the Kombewa method, the execution of which also requires considerable planning and preparation, and is extremely unlikely to be produced by accident. (When I first learned about this technique--now well over 20 years ago--I expended a fair amount of time and stone replicating it, so I speak from experience here.)

Correctly done, this results in a percussion bulb on both faces of the flake, and no ridges or arises. This is sometimes desirable since ridges can be a source of friction during tool use. Judging from the patination, this Coastal Plain chert artifact appears to be Paleoindian or Early Archaic in age, and is unique in that it this method is heretofore virtually unknown in the New World. As I noted in a chapter in "Postcards to the Past", it was occasionally used for handaxes in the Old World as well as for the distinctive obsidian tanged knives of Easter Island.

Photos by Joe Wilkinson

Tuesday, July 17, 2018

Odds and Ends from the Knapping Debris Pile

You don't have to be around me long to learn that I value self-study as an means of understanding archaeological materials and processes. Here are some items recently recovered from my scrap heap, most of which I estimate to be 20+ years old.

Top row, bifaces (L-R: coarse rhyolite, two glass, quartzite, quartz, and local metavolcanic); center row, two unifaces (quartz, Tallahatta quartzite, working edges on top), three retouched flake tools/knives (working edges on left, lower distal tip of the middle example appears to have been used as an expedient drill/perforator). Bottom left, discoid biface, judging from the step fracture (visible at top), this is an aborted small Levallois core (yeah, I went through that phase); burin spall (a diagnostic byproduct of my long-standing microdrill fascination); flake of green chert that I can't identify--while I can typically ID probably 99% of the material in my pile, this isn't one of them. It's NOT St. Louis, Ridge and Valley, moss agate from India, nor the heat-treated green component of the Coastal Plain chert. It's not right for Normanskill, either. I suspect it's an exotic given to me by someone. And a soapstone effigy bird--one of several such items made by Emma not long after she moved in.

Top row, bifaces (L-R: coarse rhyolite, two glass, quartzite, quartz, and local metavolcanic); center row, two unifaces (quartz, Tallahatta quartzite, working edges on top), three retouched flake tools/knives (working edges on left, lower distal tip of the middle example appears to have been used as an expedient drill/perforator). Bottom left, discoid biface, judging from the step fracture (visible at top), this is an aborted small Levallois core (yeah, I went through that phase); burin spall (a diagnostic byproduct of my long-standing microdrill fascination); flake of green chert that I can't identify--while I can typically ID probably 99% of the material in my pile, this isn't one of them. It's NOT St. Louis, Ridge and Valley, moss agate from India, nor the heat-treated green component of the Coastal Plain chert. It's not right for Normanskill, either. I suspect it's an exotic given to me by someone. And a soapstone effigy bird--one of several such items made by Emma not long after she moved in.

Sunday, July 15, 2018

Welcome to the blog!

Greetings all, welcome to the Media Prehistoria blog. Having largely ceased activity on Facebook, I decided I would go old-school with a platform that allows me to post items of interest. If you’re interested in primitive skills and want to keep up with what I’m doing, I encourage you to follow this blog.